-

-

Juan Sánchez: SACRED TRACES

February 8th - April 13th 2024 -

-

The cultural identity of Puerto Ricans, both in the United States as well as on the island, is a blend of principally Taino, Spanish, and African heritiges. Juan Sánchez's artistic voice embraces that hybridity. Son of a Puerto Rican family in New York, he knows the dual reality of living in a country that has long enjoyed its own independence while denying the choice for autonomy to one of its territories. Sánchez's work explores the complexity of the Latino experience in the United States, integrating the issues of race, ethnicity, political power, and religion.

Julia P. Herzberg, "Conversations in the Studio," Printed Convictions: Prints and Related works on Paper, Organized by Alejandro Anreus; Jersey City Museum, 1998

-

Early Life

Juan Sánchez was born in Brooklyn, New York on August 26, 1954. Sánchez’s parents were born in Puerto Rico–his mother, Carmen Maria Colón, in Maunabo in 1919 and his father, Juan Enrique Sánchez, Sr., in Ponce in the 1920s. After growing up on the predominantly-black southern coast of the island, they migrated to and met in New York in the early 1950s.

The artist’s family lived in various tenement buildings across Brooklyn, allowing Sánchez to experience working-class neighborhoods as they transitioned over the years from historically Jewish and Italian-American communities to predominantly Black and Puerto Rican areas. Sánchez remembers streets filled with music, vibrantly lined with grocery stores, barbershops, record stores, and bodegas. Sánchez was raised Catholic, attending church every Sunday with his brothers. Language was central to Sánchez’s upbringing: the artist spoke Spanish at home and learned English at school.

Poring over his father’s secret collection of comic books and watching cartoon television, Sánchez felt inspired to create. As a boy, he would spend hours sitting and tracing characters from American and Mexican comic strips of Superman, Batman, and Viruta y Capulina and began writing his own stories and inventing his own comics.

-

-

Poema Para Mami: Missing You, 2013, Mixed media collage on paper, 35 x 37 in

Poema Para Mami: Missing You, 2013, Mixed media collage on paper, 35 x 37 in -

Yo soy lo que soy, 1996, Signed and dated, Oil and mixed media collage on wood panel, 46 x 66 in

-

Early Education

Sánchez started elementary school at P.S. 156 in Brownsville and later transferred to P.S. 106 in Bushwick. There, his teachers noticed his artistic talent and regularly recruited him to help design and prepare the school’s bulletin boards. His art teacher, Ms. Thurston, a graduate of Pratt Institute, encouraged Sánchez to enroll in the Art Saturday program at Pratt. When the artist’s parents said they couldn’t afford the tuition, Ms. Thurston went around collecting money from his schoolteachers to cover the cost of the program and materials, arming the young artist with his own set of paintbrushes, panels, pencils, erasers, acrylic paint and oil pastels.

Sánchez went on to Halsey Junior High School in Bushwick and the High School of Art and Design in Manhattan, where he studied illustration and graphic design, determined to become a commercial artist. In his senior year, he applied and was accepted to Cooper Union as a graphic design major.

As one of only a few Black or Hispanic students admitted to Cooper Union, Sánchez faced the difficulty and discomfort of adjusting to a predominantly white institution. As the oldest of three siblings raised by a single mother on welfare, Sánchez juggled going to school full-time and working part-time to supplement his mother’s income. The Cooper Union faculty placed him on academic probation in the first semester of his sophomore year. Sánchez remembers regular visits with a social worker who eventually recommended that he start a job placement training program–but the young artist refused, knowing that accepting the offer would mean dropping out of Cooper Union. Feeling the pressure, Sánchez decided to buckle down and focus on school, hoping that his education would lead him to a brighter future.

-

Schooling

At Cooper Union, Sánchez studied with many accomplished artists in painting, drawing, sculpture, and photography, including Hans Haacke, Reuben Kadish, Charles Side, and Eugene Tolchin. The coursework transformed his relationship to art, so much so that, in the artist’s words, he “defected” from the commercial art track to pursue fine arts.

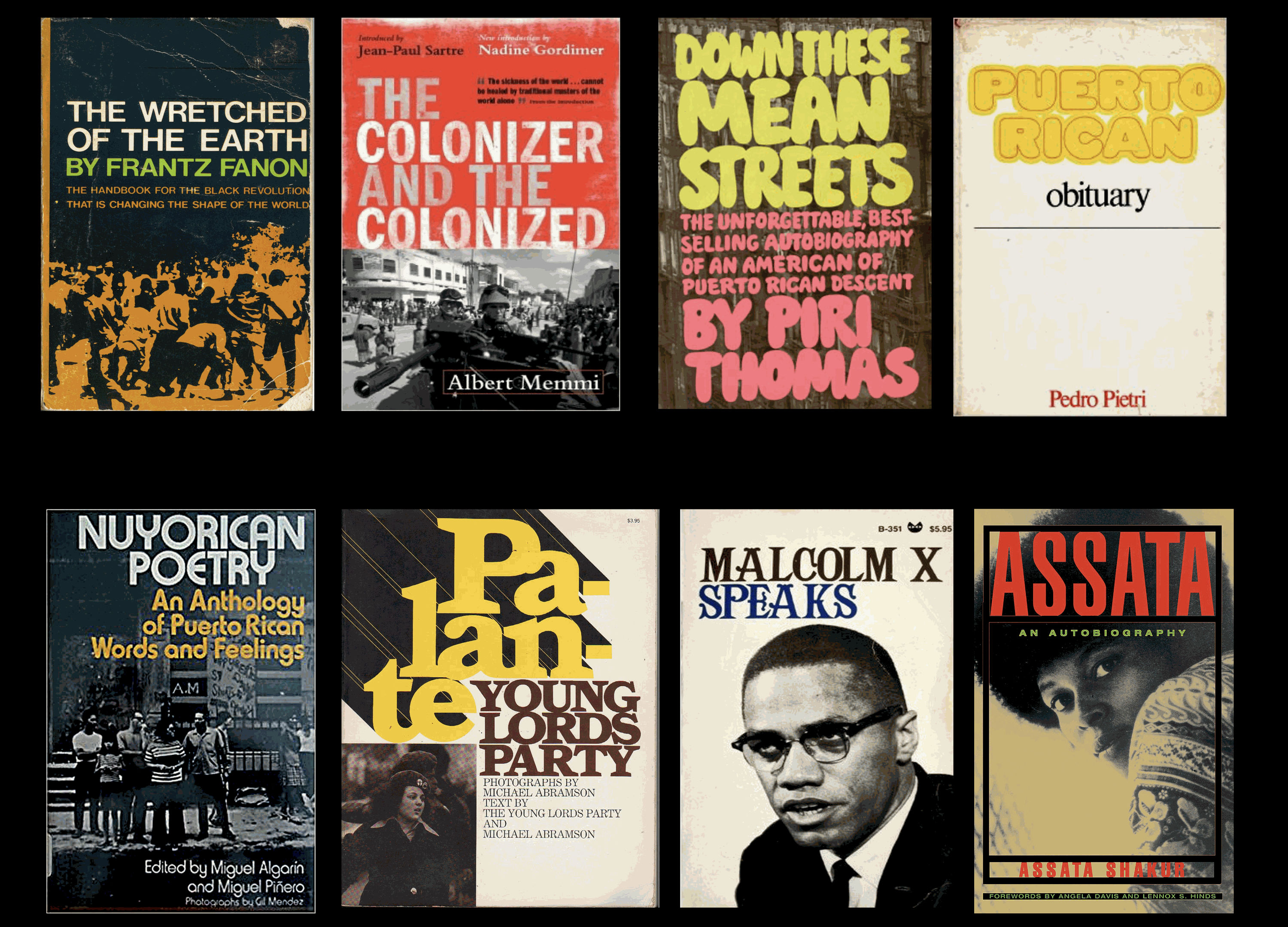

In the 1970s, while Sánchez was studying at Cooper Union, students across the City University of New York (CUNY) system demanded departments for Black and Puerto Rican studies. Armed with his Yashica camera, Sánchez traveled across the five boroughs to photograph student demonstrations, protests, and parades. At the same time, the Young Lords Party, a grassroots civil and human rights organization based in Chicago, expanded into New York City, and issued free copies of their bilingual newspaper Palante. For Sánchez, these newspapers were the first time he was able to read and learn more about the history of Puerto Rico, the island’s indigenous people, the importation of slavery, the fight against Spain, and eventual invasion of the United States. Sánchez was also a regular at the Nuyorican Poets Café, attending poetry readings and live music performances almost weekly, featuring Nuyorican, African-American, Native American, and Asian-American artists like Amiri Baraka, Jean Chang, Sandra María Esteves, Louis Reyes Rivera, Miguel Algarín, Pedro Pietri, and Juan Hernández Cruz. These experiences had a profound effect on Sánchez’s life and career, transforming the way he thought about, experienced, and created art, and his understanding of the multi-cultural Afro-Jíbaro-Taíno people of Puerto Rico. Little did he know that many years later, in 1994, Sánchez’s work would be featured in a solo exhibition at Nuyorican Poets Café, entitled Juan Sánchez: Rican/Structions: Paintings.

Their portrayal of urban landscapes across two islands–New York and Puerto Rico–reminded Sánchez of his own upbringing in Brooklyn, encouraging him to see his past life through a new lens.

With time, Sánchez also found community and inspiration at Cooper Union. One of his professors, Melita del Villar, a Cuban art historian specializing in pre-Columbian and African art, gave him the address to El Museo del Barrio in Spanish Harlem. Still in its early years, at that time, El Museo del Barrio operated out of storefronts on Third and Lexington Avenues.

On that first day at El Museo, Sánchez ran into Gilberto Hernandez, a member of Taller Boricua, “The Puerto Rican Workshop” for Nuyorican artists. Hernandez invited him to visit their artist-run studio and printshop just down the street from El Museo.

Sánchez spent the rest of the afternoon connecting with some of Taller Boricua’s founding members, including Jorge Soto Sánchez, Fernando Salicrup, and Rafael Colón Morales, enjoying the first of many days spent in East Harlem. As a result, in his final year at Cooper Union, Sánchez leaned into photography and Mexican muralism, creating on a larger scale and pulling from his own lived experiences. He made friends with many leaders of the Nuyorican and Latino arts scene, namely, Charles Biasiny-Rivera, Hiram Maristany, Adal Maldonado, and Marcos Dimas.

When Sánchez completed his undergraduate coursework at Cooper Union, he applied to the MFA program at the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University. While studying painting under Leon Golub, Sánchez met and learned from sculptor Melvin Edwards, painter Harvey Quaytman, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, and master printmaker Robert Blackburn, among many other professors and lecturers.

-

Image: Influential texts to Juan Sánchez

Image: Influential texts to Juan Sánchez -

-

The Most Cultural Thing You Can Do, 1983, Oil and mixed media on canvas, 58 x 44 1/2 in

-

Mami y su altar, 2021, Signed and dated on the reverse, Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel 12 x 12 in

-

Making and Showing

Just a few months after receiving his MFA from Mason Gross School of the Arts, Sánchez’s graduate work went on to be featured in major museum exhibitions at the Bronx Museum, the New Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. A number of these opportunities came through recommendations from his professors and mentors, namely, Leon Golub and Melvin Edwards. At the time, Sánchez was still living at home with his mother and storing his works in the building hallway. His work was, and continues to be, rooted at the intersection of the personal and political, often bringing attention to the Puerto Rican independence movement and calling for the release of political prisoners and nationalist activists.

In the early 1980s, Sánchez was also featured in group exhibitions at Cayman Gallery, founded by the nonprofit group Friends of Puerto Rico in collaboration with Puerto Rican activists, and at Group Material, a Lower East Side exhibition space and home to the eponymous conceptual artist collective. In 1985, Group Material invited Sánchez to participate in Americana, their site-specific group presentation at the Whitney Biennial. Eight years later, in 1993, Whitney Biennial curators asked Sánchez to present his work as a solo artist. He has since been featured in over seven shows at the Whitney Museum and has multiple works in the Museum’s collection.

From 1981 to 1983, Sánchez worked with Henry Street Settlement as an artist-in-residence and curator of two exhibitions–Beyond Aesthetics and Evidence: Twelve Photographers–both dedicated to political art by Black and Latino artists. While organizing these shows, Sánchez met Puerto Rican artist Papo Colo, who later teamed up with Jeanette Ingberman to found Exit Art, an experimental cultural center that presented visual art, theater, poetry, music, film, and video work. Sánchez established a long-standing, fruitful relationship with Colo and Ingberman. In 1987, Exit Art hosted a solo exhibition of Sánchez’s work, entitled Guariquen: Images and Words Rican/Structed. The following year, at only 34 years old, Sánchez was awarded the highly prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in Fine Arts from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. In 1989, Exit Art organized a second exhibition of Sánchez’s work, Juan Sánchez: Rican/Structed Convictions. The solo show traveled to the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder and to the Massachusetts College of Art in Boston, with an accompanying catalog written by Lucy Lippard & Shifra Goldman.

Juan Sánchez’s work has also been included in two major Smithsonian traveling exhibitions. Sánchez was a part of the 2011 show at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, entitled Multiplicity, alongside notable artists like John Baldessari, Chuck Close, Sol LeWitt, Julie Mehretu, Kiki Smith, and Kara Walker. The groundbreaking 2013 exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art at the Smithsonian Museum of Art traveled to eight cities across the United States in four years. The Smithsonian Archives of American Art also conducted two interviews with the artist, first in 2018 and then in 2020, as part of their Archives of American Art Oral History Program, started in 1958 to document the history of visual arts in the United States.

Sánchez’s first and only solo exhibition in his native borough occurred in 2015 at BRIC House in Downtown Brooklyn. The exhibition featured some 30 works including large-scale mixed-media paintings, a selection of works on paper, and video. There was an accompanying exhibition catalog by curator Elizabeth Ferrer and an interview by Art21 Executive Producer Eve-Laure Moros-Ortega. The exhibition was also featured in a collaborative video program, CALL/VoCA, produced by Voices in Contemporary Art (VOCA) and the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Creating a Living Legacy (CALL) Program.

-

-

Juan Sánchez, Unknown Boricua Streaming, 2010

It took thousands of still images and collages to produce UNKNOWN BORICUA STREAMING: A Nuyorican State of Mind. Assertively fast-pace and densely layered, my stream of consciousness is at the heart of this video. These collaged elements are charged with an array of images, iconography, comic book characters, celebrities, Catholic, African, and Taino symbolism, and global historical and political events. Like a stream of consciousness, these images ignite, emerge, push, and overwhelm with split-second twists and turns. Graffiti, patterns, and color flashes mix and flap through places, time, family and historical photos, and newspaper clippings. Colonialism, genocide, civil rights, human rights, and global struggles for freedom are presented with rapid overlapping successions. A recurring background are collages of female/male nude figures, their heads draped with a Puerto Rican flag boxed within a disjointed grid. Here, I represent a colonized nation and its political prisoners. UNKNOWN BORICUA STREAMING: A Nuyorican State of Mind is intended to stimulate the viewer to reflect, retrieve, determine, share, and transcend our human experience, and to continue the fight for change. The struggle for equality, social justice, freedom, and peace continues.

Juan Sánchez, Juan Sánchez: ¿What’s The Meaning of This? Painting | Collage | Video, BRIC, 2015

-

Living and Working

While leading tours and developing family workshops in the education department at the Queens Museum, Sánchez suggested that the workshops expand beyond the visual arts to include music, dance, and theater. The Museum decided to hire a performing arts specialist to help improve the department’s syllabus and curriculum. When interviewing candidates, Sánchez met his future wife, Alma VIllegas, a graduate student at NYU in theater education. They married on March 13, 1987 and gave birth to their daughter, Liora Sánchez-Villegas on September 2, 1990, just days before Sánchez started teaching at Hunter College.

The artist’s mother, wife, and daughter became central figures in his work. Para Carmen María Colón is one of many examples. The mixed media print combining lithography, handcoloring, and chine college is an homage to his mother. At the top center, Sánchez pasted a self-portrait drawing by his mother of her standing next to the Puerto Rican Flamboyán Tree, flanked by a photograph of his mother looking out at their backyard and a photograph of a shelf in a botanica shop for spiritual and religious healing, with a black rag doll similar to the ones his mother made.

Sánchez often turned to the family scrapbook for material inspiration. For his 1995 self-portrait-of-sorts, Yo soy lo que soy, the artist reprinted a photograph from his fifth birthday party, wearing a suit and birthday cone hat. At the center, overlaying the birthday collage, is a superhero figure named Astro Boy, harkening back to the young artist in the photograph who spent hours on the floor tracing and drawing his own superhero comics while watching cartoons.

Looking to expand his mixed media practice, Sánchez started opting for large, 6x6 ft wood panels over traditional canvas. He began screwing, nailing, and hammering into wood, attaching found materials and adding more two-and-three dimensional layers to his work.

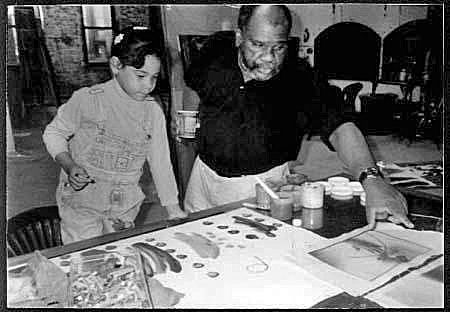

Fresh off the Guggenheim Fellowship and wanting to focus on his art, Sánchez left his administrative position at Cooper Union’s Office of Admissions, against the advice of many friends and colleagues. For a few months, Sánchez was comfortable being unemployed and living off of the Guggenheim stipend, but all of sudden, “the money was running out [and] Alma [his wife] got pregnant.”26 He received a phone call from Hunter College about the job application he submitted almost a year prior. He started teaching at Hunter just a few days after his daughter was born, over 30 years ago, and has mentored and taught hundreds of artists in Hunter’s undergraduate and graduate programs. He finds teaching incredibly gratifying and loves assignments that ask students to rely on their senses: drawing and painting from observation; drawing and painting from their imagination; feeling mystery objects in a paper bag and drawing from touch, texture, and temperature; drawing while listening to music and in response to poetry, among many others.

-

-

-

-

-

Mami y Chacon, 2021, Signed and dated on the reverse, Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel 12 x 12 in

-

Recent Work

As an artist and activist who has spent his entire life in Brooklyn, Juan Sánchez’s work is personal, political, and uniquely New York. Almost all of his work over the last three decades has been created in DUMBO. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, Sánchez began mining his own personal archive and shifted to working on a smaller scale, with his most recent work on 12x12 inch panels, many of which are featured in this exhibition.

-

Collage Panels

“During the time that I was at home recuperating [from cancer], I got very frustrated because I just couldn't continue painting at the scale that I was. So, I thought of an idea of working on 12-by-12-inch square panels, and the images that I was using as collage elements are images that people are already familiar with because I used it on several occasions in past works...

I went to my storage to look for something and I found boxes of negatives, contact prints, and prints, silver gelatin prints of work that I'd done in the '70s and the '80s because there was a time when I was doing my painting on one end and then I was also doing a lot of street photography. I was documenting my neighborhood. I was documenting similar neighborhoods, like in El Barrio in East Harlem. Going back to a lot of the Puerto Rican, the Latino communities, and just documenting that environment. Of course, at that time most of the people there were Puerto Ricans. So, so I have a whole body of photographic works that I shot from the mid-'70s into the beginning of the '90s, and I haven't looked at them since. I had a one person show of these works back in 1979, but I never exhibited these prints again.” [1]

[1] Oral history interview with Juan Sánchez and Fernanda Espinosa, July 30, 2020, Smithsonian Archives of American Art -

An interview with Juan Sánchez conducted 2020 July 30, by Fernanda Espinosa, for the Archives of American Art's Art Pandemic Oral History Project at Sánchez's home in Brooklyn, New York.

Juan Sanchez, Pandemic Oral History Project, Archives of American Art, 2020

-

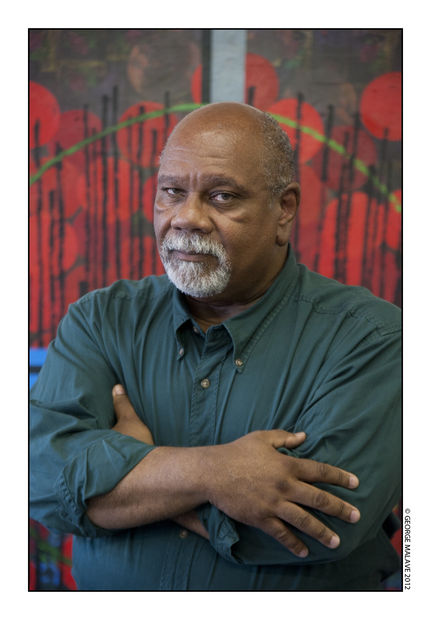

Portrait

Portrait -

-

-

-

Juan SánchezAlma Mía, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

Juan SánchezAlma Mía, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

53.3 x 50.8 cmEdition of 3 with 2 artist proofs -

Juan SánchezFlor, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

Juan SánchezFlor, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

53.3 x 50.8 cmEdition of 3 with 2 artist proofs -

Juan SánchezTired Leader, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

Juan SánchezTired Leader, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

53.3 x 50.8 cmEdition of 3 with 2 artist proofs -

Juan SánchezYoung Lords Warriors, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

Juan SánchezYoung Lords Warriors, 2009Archival pigment print on watercolor paper21 x 20 in

53.3 x 50.8 cmEdition of 3 with 2 artist proofs

-

Juan SánchezMami y Cachon, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezMami y Cachon, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm -

Juan Sánchez, Untitled, 2021

Juan Sánchez, Untitled, 2021 -

Juan SánchezLas Tres Marias, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezLas Tres Marias, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm -

Juan SánchezMami y su Altar, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezMami y su Altar, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm

-

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm -

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm -

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

Juan SánchezUntitled, 2021Vintage silver gelatin print and mixed media collage on wood panel12 x 12 in

30.5 x 30.5 cm

-

-

Diptychs and Triptychs

"Along the way, I started working on many of the individual 12-by-12-inch pieces. Then I started making a diptychs and triptychs out of them. So, from this initial project, there's this spin-off where I started making diptychs, triptychs, and even individual pieces."[1]

[1] Oral history interview with Juan Sánchez and Fernanda Esposa, July 30, 2020, Smithsonian Archives of American Art

-

Cries & Whispers

-

Installations and Public Art

-

In the Studio with master printer Maryanne Ellison

"This idea that the shop in St. Louis was a place where an artist could produce some of his/her finest work was certainly substantiated by Juan Sanchez, who returned in 1995 to Washington University to make a print so complex that it would take twenty-six months to complete. Eventually Sol y Flores Para Liora (Sun and Flowers with Liora) would win a Grand Prize at the Latin American Print Biennial in San Juan in 1998. In this print, Sanchez’s daughter, Liora, wears a small wedding dress and stands centered in the upper part of the composition. She is surrounded by five depictions of her own hands. Nine small silk roses are placed above her head. In the area below Liora are spirals (the Puerto Rican Taino Indian symbol for the sun), other Taino petroglyphs, and one large multi-colored flower. Through this mélange of elements, the past (immediate and distant), the present, and the future are all given space in this image. Significantly, Sanchez was referring to his heritage, his culture, and the traditions that have become so much a part of his persona.

Perhaps the best characterization of this project and, indeed, the entire print shop at Washington University, is found in the words of Maryanne Ellison Simmons, the master printer with whom Sanchez worked on this visit. When the work was finished, she wrote to him, "As ever, this has been a wonderfully complicated project. We’ve worked hard … When we rest up, let’s do it again!"(1) Such enthusiasm permeated the shop beginning at the top and filtering down. The fearless attitude of tackling each difficult project supplied the necessary ingredient for successfully producing unique works of art with the stamp of Island Press. Sol y Flores Para Liora is the combination of a photolithograph, collagraph, collage, and hand painting on handmade paper, proving that nothing is done the "easy" way in St. Louis."

Marilyn Kushner, Curator and Chair of the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1994-2006 -

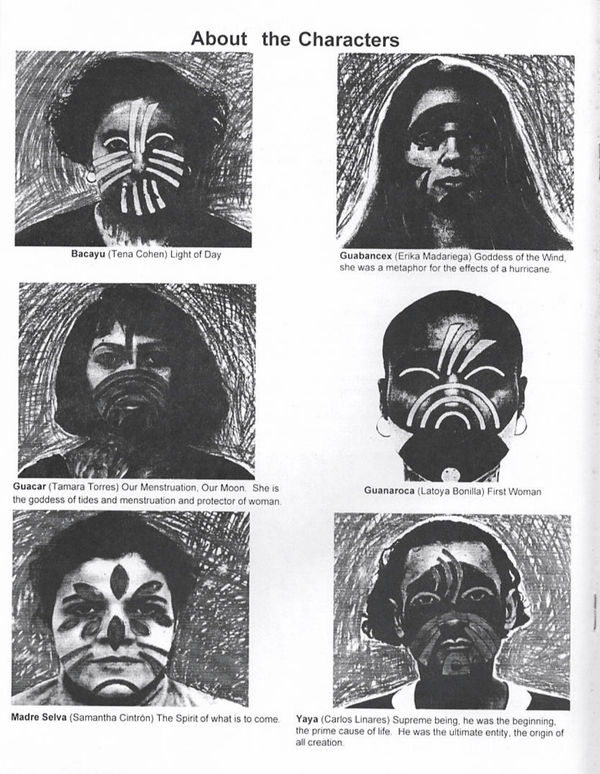

Costume and MAKEuP Design

-

In 1996, Juan Sánchez, alongside Jolie Guy, designed the costumes and makeup for actors in the performance Madre Selva: From Life to Spirit, conceived, written, and directed by Sánchez’s wife Alma Villegas. The play is a ritual performance dedicated to the Cuban artist Ana Mendieta, where her philosophy on life and art, her explorations of Taíno and African customs, and her earth-body artworks merge with the ultimate resolution of her return to nature. The one-hour long performance blends different forms of artistic expression: live music, dance, imagery, and poetry.

Sánchez and Villegas befriended Mendieta during the 70s and 80s downtown New York art scene. In 1981, Sánchez’s and Mendieta’s works were chosen for an exhibition during which they became friends. Sánchez even chose a wall installation by her for the exhibition RITUAL & RHYTHM: Visual Forces for Survival that he curated at Kenkeleba House Gallery in the Lower East Side, where Villegas and Mendieta met. After the news of Mendieta’s sudden death in 1985, as an homage to their artist friend, Villegas was motivated to create her performance, and Sánchez was motivated to contribute. Sánchez describes his thoughtful process for designing the costumes and makeup in the performance’s program as a part of a conversation with José Candelario.

“I came to realize that the process of designing the makeup and the costumes was just as organic as the process of Ana’s work. I decided not so much [to] try to capture her work and to translate that into costume design or makeup, but to deal with the Taíno essence of design, and try to bring that to life. The makeup I am designing for each of the women is to integrate the facial personality of the individuals in the production with their characters. They all have different features, have different faces and are so attractive and beautiful in different ways. I am approaching the makeup with indigenous yet contemporary designs so as to enhance their features rather than give them masks to cover their faces.

The same thing with the costumes. They are painted, directly on top of the dancer’s bodies. What’s most important is that the design for the faces and the costumes will maintain an organic quality. The color that is going to be dominating will be brown, which represent the earth. I’m hoping that my design will take the spirit and essence of Ana’s work to another level within the context of the theater production.

As a painter I am creating art that is motionless. They’re objects that do not move, but now in designing makeup and costumes on bodies that will be moving from one end of the stage to the other, the art I’m creating is taking on a whole other life of its own. And that has a direct affinity with Ana Mendieta’s work. Because, in addition to doing her sculptures, her performance art entailed movement and sound and the spectator becoming a witness to her act. I would like people to walk away with the essence, character and spirituality of what we believe Ana Mendieta was all about. I want them to share their experience with other people as a testimony of what they have [...seen] and felt in their enlightenment from Madre Selva.”

-

-

-

Museum Exhibitions

-

Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art

Smithsonian American Art Museum October 23 2013 - March 2, 2014 Exhibition Catalogue -

Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century

The Museum of Modern Art 1992 Read the Catalogue -

¡PRESENTE! THE YOUNG LORDS IN NEW YORK

Bronx Museum | El Museo del Barrio | Loisaida The Bronx Museum of the Arts (July 2 – October 18, 2015), El Museo del Barrio (July 22 - December 12, 2015), and Loisaida Inc. (July 30 – December 1, 2015) -

Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell

UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press Los Angeles |The Getty Foundation 2017 -

Mito y Magia en América: Los Ochenta

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey, A.C.Learn More

-

-

Publications

-

"Juan Sánchez: Pursuit of an Island," Jonathan Goodman, 2020

-

Juan Sanchez: What's The Meaning of This?

-

Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century

Edited by Edward Sullivan 1996 -

Mixed Blessings: New Art in a Multicultural America

Lucy R. Lippard 1990 -

Freedom Within

-

All My Ancestors The Spiritual in Afro-Latinx Art

The Printed Image Gallery Brandywine Workshop and Archives February 10–June 18, 2022 Read Catalogue Here -

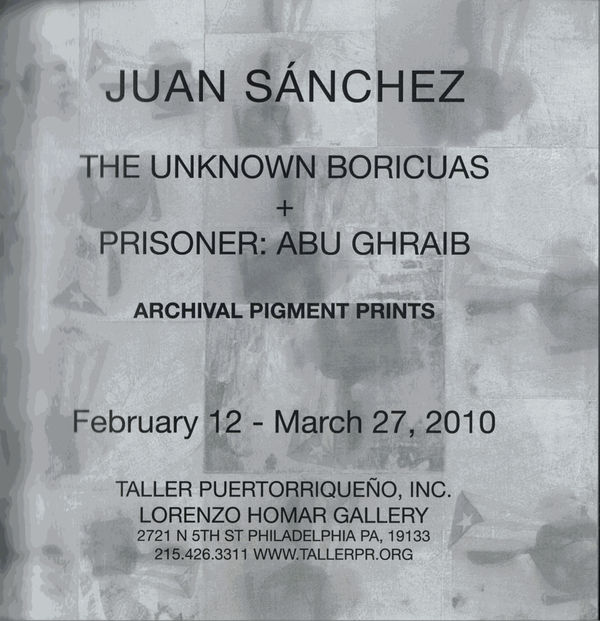

The Unknown Boricuas + Prisoner: Abu Ghraib

Lorenzo Homar Gallery February 12 - March 27, 2010 -

On the Wall: Four Decades of Community Murals in New York City

University Press of Mississippi / Jackson Read More -

Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century

The Museum of Modern Art, New YorkJuan Sánchez was included in The Museum of Modern Art's group exhibition Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century. -

Mito y Magia en América: Los Ochenta

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de MonterreyJuan Sánchez was included in the group exhibition Mito y Magia en América: Los Ochenta, curated by Miguel Cervantes and Charles Merewether.

-

-

-

Video

-

Our America Audio Podcast - Juan Sánchez, "Para Don Pedro"

"Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art" at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2013This audio podcast series discusses artworks and themes in the exhibition 'Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art' at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. In this episode, artist Juan... -

Art Matters: Juan Sánchez

Art Matters, Fitchburg Art Museum, 2020Reflect on the powerful work of artist, activist, and educator Juan Sánchez in an interview with Fitchburg Art Museum's Terrana Assistant Curator Marjorie Rawle. Watch this exclusive video to learn... -

Juan Sanchez, Pandemic Oral History Project

Archives of American Art, 2020An interview with Juan Sánchez conducted 2020 July 30, by Fernanda Espinosa, for the Archives of American Art's Art Pandemic Oral History Project at Sánchez's home in Brooklyn, New York. -

CALL/VoCA Talk: Juan Sánchez

On Wednesday, November 18, 2015, CALL artist Juan Sánchez was interviewed by VoCA Program Committee member and Associate Conservator at Modern Art Conservation Jennifer Hickey at the Bronx Museum of...

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Juan Sánchez

Current viewing_room